If you spend any time in the countryside, you’ll likely be familiar with the principle of “leave no trace”. At its heart, this sets out the framework for ensuring that your presence does not cause a problem for others, and if you’re stealth camping it ensures you’re able to go undetected.

In the digital landscape, footprints can accumulate even faster than in the real-world and the traces you leave behind can become a nuisance for others and a security issue for you.

In this in-depth article, we’ll explore what digital footprints you might be leaving, how people can use this information against you, introduce you to some common and free tools, and provide actionable steps you can take to reduce your digital footprint.

Open-Source Intelligence

We hear a lot in the media about companies collecting our personal data and tracking us online. Whether it’s cookie consent or other aggressive trackers that follow you around as you browse the web, we’re increasingly aware that our personal activity is monitored by someone. But we may not be aware that this is also the case in our businesses too. Every time you create a new server, purchase a domain name, or even create a new email address, someone will likely notice and record that and make it available.

OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence) is the term used to describe the collection and analysis of freely available information. Even though you may not have heard the term, almost certainly you do this regularly – any time you look up a company or product, you’re performing OSINT. When researching a company you may read their website, checking out their social media presence, and look at their submissions to Companies House. That’s all OSINT.

A difference between that and what we’re going to explore is that in the above example, this is all information that the company controls and want to be in the public domain. But there’s a heap of information gathered and collected by other people that we have no control over and may not even know exists.

Domain name records

OSINT covers a wide range of information but, in this article, we’re going to focus on domain name records (DNS records). Why? Because we’re very good at creating things, and a lot less good a tidying up! Checking our DNS records is a great housekeeping exercise that can help us find infrastructure that we no longer need. Shutting these instances down reduces our footprint, improves security, and reduces cost. And that’s a win in anyone’s books!

A worked example

In a recent security review, we discovered an organization had a forgotten development API endpoint exposed to the internet. This endpoint, while seemingly harmless, contained production database credentials in its error messages. Despite the company’s otherwise robust security measures, this single oversight could have led to a significant data breach. Through a structured DNS audit like the one outlined below, they were able to identify and remedy this before any breach occurred.

We regularly find similar issues even in security-conscious organizations – from exposed internal documentation to development environments containing sensitive data.

This isn’t an isolated case. We regularly find similar issues even in security-conscious organizations – from exposed internal documentation to development environments containing sensitive data.

1. Enumerate domain name records

Whenever I’m conducting a security review for a client, subdomain enumeration is one of the first things I’ll perform. Two great tools here are Subdomain Finder (https://subdomainfinder.c99.nl), and SecurityTrails (https://securitytrails.com).

Both have their uses and a both free to use, but in this example, we’ll use Subdomain Finder as it has a simpler interface. SecurityTrails and Subdomain Finder often show different results, so it’s useful to explore multiple tools and SecurityTrails offers some extra features, such as being able to see a full DNS history.

Using Subdomain Finder, simply enter the top-level domain you’re wanting to check (such as google.com) and click Start Scan. Personally, I like to also check the “Private scan” option so as to not make the results of the scan publicly listed. If there are issues, you don’t want to shout about it!

Here’s a screenshot of what Subdomain Finder looks like after scanning google.com:

You can see a list of subdomains found, their IP address, and whether they are using Cloudflare (a popular DNS and security platform).

If you have multiple domains, you should perform this check for all top-level domains you own.

For each subdomain that is found, we will ask:

- Is this domain still needed?

- Does it need to be public?

- Is it up to date?

- Is it secure?

2. Is the domain still needed?

You may find that there’s old, forgotten domains that you no longer need. Once confirmed as no longer in use, these can be decommissioned and removed.

What are the risks?

Old, obsolete domains can harbour outdated software or unnecessary data. Outdated software may contain known vulnerabilities—serious security risks waiting to be exploited. Additionally, retaining old data can become a compliance issue, potentially breaching regulations like GDPR, which can result in significant fines and loss of customer trust.

Why has this happened?

Finding domains that are no longer needed usually means there’s a gap in your development lifecycle processes. A robust development lifecycle should include how to determine when a project has ended, and steps needed to decommission it.

What’s the benefit of fixing it?

- Improve security through reducing attack surface

- Improved compliance with data protection legislation and best practice

- Cost savings from switching off unnecessary services

Action plan

- Confirm with relevant teams that the domain is indeed obsolete.

- Back up any necessary data tied to the domain.

- Decommission services, remove DNS records, and cancel associated subscriptions.

3. Does it need to be public?

There are two aspects to this. First, does even just the name of this domain give away information that should be private? And second, should access to this domain be public?

What are the risks?

In some cases, the name of a domain can give away more information than you want to. You could leak:

- Details of your infrastructure – e.g. cisco.mydomain.com, or mysql.mydomain.com

- Confidential client information – e.g. clientname.mydomain.com

If the domain doesn’t require public access, it shouldn’t have it. For example, publicly accessible test or development environments may:

- run non-production or untested code which could be insecure.

- have extended debug information enabled which could disclose information about the software or infrastructure.

- have test accounts with weak passwords.

Why has this happened?

Usually this is because of an assumption that obscurity is secure enough. If your domain name isn’t publicized anywhere, then how can people know about it?

What’s the benefit of fixing it?

- Improved security through removing public access to private services.

- Improved security through reducing confidential or sensitive information from domain names.

Action plan

- Review the domain name for information disclosure.

- Check with all stakeholders whether the domain is required to be public.

4. Is it up to date and secure?

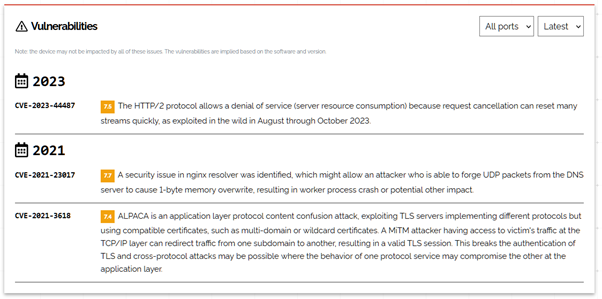

For the final steps, we are going to use a new tool, Shodan (https://shodan.io). Shodan is a search engine for information about internet-connected devices. If your server is connected to the internet and is publicly accessible, there’s a very good chance it will appear on Shodan. We will use it to check software versions that your servers are running and details of open ports.

For each subdomain, simply type the domain name or IP address into Shodan’s search box. If you’re using a proxy such as Cloudflare for your subdomains, search Shodan using your server’s real IP address. Shodan will return any information it has about what software your server is running and then cross-reference that with vulnerability databases.

What are the risks?

Any open port on your server is a point of weakness that can be attacked. Only ports that are essential should be open to the public. For a web server, these are usually 80 and 443. Any other ports should be closed.

Outdated software often contains security flaws that can be exploited. A serious vulnerability can fully compromise your server.

Disclosing unnecessary information about the software and versions that your server is running gives important information to attackers and offers you no benefit.

Why has this happened?

These issues point to ineffective policies and procedures, such as software hardening and patch management or poor change management control.

What’s the benefit of fixing it?

- Improved security through removal of vulnerable software.

- Improved security through reduction of attack surface.

- Improved security through reduction in information disclosure.

Action plan

- Review security policies and implement revisions as needed.

- Ensure regular software updates.

- Implement security baselines for all projects.

- Review open port requirements and close ports not required to be public.

Wrapping up

That concludes our first audit of your DNS footprint. This process may have uncovered some surprises and a fair few issues to address. If you find yourself with a lengthy checklist, don’t despair! The steps outlined here have equipped you with the knowledge to make meaningful improvements to your operational security.

Remember though, this initial audit is just the beginning. To maintain a secure environment, you should turn this process into a regular review.

For smaller estates, performing this audit quarterly might be sufficient. Organizations with larger footprints should consider automation tools or services.

Going deeper

While we’ve focused on DNS records, OSINT covers a lot more. I hope this article has highlighted how much information about our infrastructure is publicly available.

This type of audit should sit within a broader security and assurance program. That may seem a way off, but we’ve covered a lot of the basics here – setting policy, developing processes, gathering evidence of compliance, and making improvements based on findings is the core of many frameworks such as ISO 27001, CAF, and NIST.

A basic security program might start with:

1. Regular DNS audits (as outlined in this article)

2. Asset inventory management

3. Vulnerability scanning and patch management

4. Access control review

5. Security awareness training

Each of these components builds upon the others, creating layers of security that protect your organization. Whether you’re just starting your security journey or looking to enhance existing measures, the key is to begin with understanding what you have – which is exactly what this DNS audit provides. We’ll explore these other aspects in future articles.

When to consider professional help

While the tools and processes outlined here are valuable for initial assessment, certain situations may warrant expert assistance:

- If you discover multiple exposed administrative interfaces or sensitive data

- When your infrastructure spans multiple cloud providers or includes legacy systems

- If you’re preparing for compliance certification (ISO 27001, SOC 2, etc.)

- When resource constraints prevent thorough internal security reviews

Professional security consultants bring specialized tools, experience from diverse environments, and can often spot patterns that indicate deeper issues. Think of it like maintaining a car – while regular checks are essential, sometimes you need an expert mechanic’s perspective to spot developing problems before they become serious.

If you have questions about DNS auditing or would like to discuss how these findings apply to your organization’s security posture, we’d be happy to help – just get in touch.